Companies organized in an agile way seem to be ahead of the game today. So, why haven’t we all already been organized in this way?

Recently, on a conference, I talked

to a friendly attendee. Agile, she said, appealed to her personally, she found it interesting and helpful. But for her and her department’s job, she regretted, agile approaches were out of the question.

After all, in her department, it’s all about routinely processing rather uniform tasks. She would very much welcome agility for projects in which she is also partly involved, but not for her department’s routines.

While I am certainly often confronted with the misconception

that Agile was invented for projects, I confess that I am always a bit clueless. What should I do? Should I argue?

Should I say that it is precisely the patterns of thought and action that are not regularly reviewed, precisely the entrenched, unconscious routines, that get teams, departments and entire companies into trouble. In general. Especially nowadays. They turn out to be a threat to them.

Because they make you feel safe when you are not..

It is precisely these routines that open up huge opportunities for competitors.

So should I say that Agile is particularly effective and important with routines? Because Agile teams are all about asking themselves again and again whether they are still doing the right thing, whether they are still good enough, in other words: whether the routines are still right?

Should I be doing this?

Better not. Who wants to be preached to?

After all, we all have the right to find our own way and make our own experiences (including the sometimes adventurous missteps it takes).

So I held back this time again. Even though it was hard for me this time. Again. (It gets easier each time).

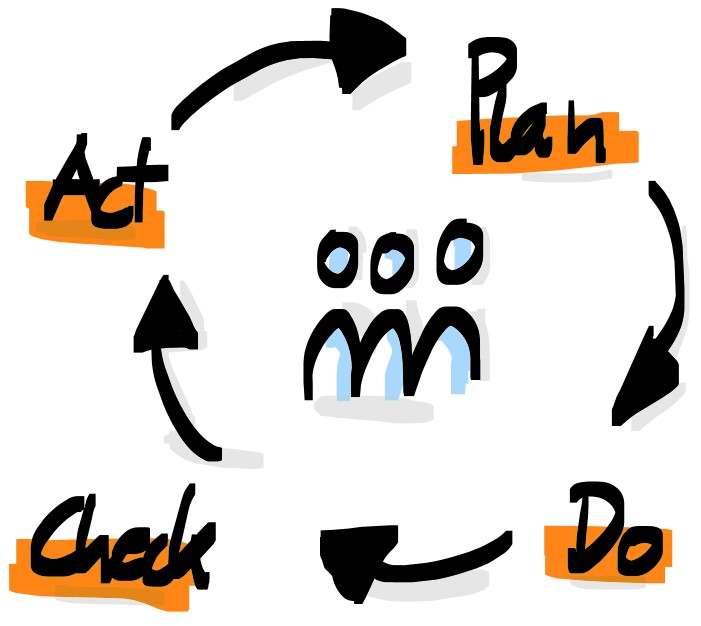

Any Agile working framework

be it Lean Startup, Design Thinking, DevOps, Kanban, Scrum, etc., follows the same basic empirical, experience-based organizing principle (and the same value creation philosophy): in manageable steps, recurring, and focused on a big goal:

- plan

- do

- check (study)

- adapt./1/

Accurately speaking, this is the universal, evolutionary principle of learning and surviving that each of us has known since the first moment of our lives – at least since we first touched the very hot hotplate.

Agile consistently transfers this learning principle

to the organization of collaborative tasks. Each agile working framework does this in its own way, with certain emphases and with certain goals.

What they all have in common, however – and here they differ fundamentally from those prevailing hierarchical structures and organizational principles that emerged in the machine and production age of the last century – is that all working frameworks prioritize the collaborative element as a basic condition.

And this is not because Agilists are better people (which has yet to be proven) or because, say, this kind of collaboration feels better (which has already been proven).

But simply because today, in the dawned service age, it is all about optimizing value. Which means pecuniary and/or other profit. (“Maximum outcome, minimum waste.”).

And for this it simply needs different approaches than the ones around.

Agile, therefore, always and consistently turns as many people as possible

to participants. May it be managers, staff or any kind of stakeholder, first and foremost of course the customers. (We are talking about taking part in decision making, value creation, taking over responsibility, motivation etc.).

For this purpose, they are given a structural framework (financial, organizational, thematic, creative, visionary, etc.). In an self-organized way they repeatedly (respectfully and on an equal level) exchange information (feedback) about the what, the how, the current status and the next concrete steps in certain rhythms.

As a consequence, results are gradually developed in an organizationally maximally fast, flexible and seemingly incidentally appreciative and motivating way, which satisfy everyone as much as possible.

(And if this does not succeed, undesirable developments can be corrected relatively easily and quickly).

However, although each of us know this learning principle by heart

although each of us today has a very large expertise in how to organize well,/3/ although the successes and advantages of agile companies are visible and tangible for all of us today, and although, on the other hand, things are increasingly not going quite so smoothly for us, slower, more complicated, more inflexible, more self-centered, more annoying, more conflictual, etc., so despite all this, we find it difficult to take the obvious, the agile step.

Why?

For me, it is because

we are (as so many times) victims of an all-too-human pattern of behavior:/4/ Despite many warnings and existing rational insight, we still lack (for us) good, convincing motivational reasons, we lack the real, our own urgency to break away from the existing but expiring organizational success model of the last century.

What is tough enough for each of us individually doesn’t get any easier in groups. (“It’ll work out.”, “It’s all worked out well so far!”, “It’ll be fine.”)/4/

The successful model called for

striving for structural and routine stability. That`s what the circumstances of the time demanded.

So they relied on division of labor (silos) and on management (“command and control”), on maximally efficient, routinized and standardized processes (“best practice”), on the expertise and strength of the individual (“specialism”, “it’s up to you!”) and on extrinsic motivators (bonuses, existential fear, compulsion).

Until the turn of the millennium, this worked just fine economically

Until the turn of the millennium, this worked just fine economically

(ecologically, it probably looks different) and was therefore also very desirable for a long time.

Today, however, this form of corporate management is developing not at all slowly into a relatively large structural risk that can (and happily does) pose an existential threat to organizations as a whole

Because unlike back then, today we are dealing with much more unsteady times and changed environments. Complexity and rapidity are just two challenges for organizations here, albeit particularly large.

However, a multitude of other issues can be effortlessly added here, which are developing at a similarly rapid to radical pace:

- Differentiation of markets (subcultures),

- Skilled labor crisis and gender shift in the workplace (demographic change),

- Change in authority,

- Generational and motivational divide (“the disappearance of patriarchy”, “Generation X, Y, Z”),

- Democracy crisis including the reorganization of national and international state systems,

- And – certainly not to GOOD-last: the uncertain and unpredictable environmental and climate developments.

Note: All these are not future predictions.

They are today’s phenomena that affect us all (!). Today. And we have to face them all (!) today. Today means: now. Every day.

Will we succeed with the previous organizational means? Questionable.

Will we succeed with the previous organizational means? Questionable.

Albert Einstein is believed to have once said that you can’t solve problems with the same mindset that created them. There is something to be said for the fact that this also applies to ways we organize our work.

So why aren’t we already doing things differently? Are things still going well enough? Or shouldn’t we start to approach things differently?

Notes

- /1/ See also: Deming circle, e.g. here on Wikipedia

- /2/ Why? Because the value creation of a service is decided differently, by others and in other places than the value creation of a product. Mainly, then, because the push approach is no longer as reliable as it once was.

- /3/ Probably due to the countless restructuring and efficiency programs of the last decades.

- /4/ “This is expressed in the tendency of most people to carry on as before, even when change would definitely bring them advantages. We have given the reason for this seemingly irrational persistence: Continuing as before carries a strong reward in the form of a desire for routine, for being an expert, for maintaining status. Added to this is the fear of the new, which always carries with it the risk of failure. This creates a high threshold in many people, which the reward value of changes in one’s own behavior must overcome.” Gerhard Roth (see below).

- /4/ See also: Dörner, Dietrich: The logic of failure. Strategic thinking in complex situations. Reinbek, 2007.

Literature

- Dörner, Dietrich: Die Logik des Misslingens. Strategisches Denken in komplexen Situationen. Reinbek, 2007.

- Kotter, John P.: Accelerate. Building Strategic Agility for a Faster-Moving World. Boston, 2014.

- Roth, Gerhard: Persönlichkeit, Entscheidung und Verhalten. Warum es so schwierig ist, sich und andere zu ändern. Stuttgart, 2011.

- Spitzer, Manfred: Lernen. Gehirnforschung und die Schule des Lebens. Heidelberg, 2007.

- Verhaeghe, Paul: Autorität und Verantwortung. München, 2016.

Until the turn of the millennium, this worked just fine economically

Until the turn of the millennium, this worked just fine economically Will we succeed with the previous organizational means? Questionable.

Will we succeed with the previous organizational means? Questionable.